Morty

I was eighteen when I met Morty (short for Morton). I had just gotten my first job and was working for the Professional Placement Center at the New York State Employment Service. Like every office, we had professional and support staff. I was part of the support staff. The professional staff were all employment counselors, whose job it was to fill openings in myriad professional fields. Morty was the supervisor of the “psych” unit, which sought to fill job openings for psychologists and psychiatrists.

Morty, a stutterer, was of short-to-average height and somewhat overweight, with a slight double chin and graying hair. When I first met him, he tried to ask me my name but couldn’t get past the first word. He said, “Wha . . . wha . . . wha . . . wha . . . .” I came to his rescue and said, “Spit it out. Come on, spit it out.” He burst out laughing and said, “Most people get uncomfortable when I stutter. I like you.” I smiled. It never occurred to me to be uncomfortable. He knew he stuttered, so what was the big deal? We became fast friends. Morty’s stuttering was unpredictable. He could speak uninterrupted for a couple of paragraphs and then suddenly “wou, wou, wou, wou wou, wou, wou. . . ld you like to go to lunch?”

I didn’t know it at the time, but Morty, who was almost twenty years my senior, saw me as someone he could “educate and mold.” In his mind, he was the Henry Higgins to my Eliza Doolittle, but, unlike Eliza, I spoke well, which meant my education would involve all things cultural as far as he was concerned. One day, as I approached Morty’s desk with a file, he said, “You know, you would be real pretty if you wore makeup and lost a little weight.” Neither issue was on my radar, but both ideas seemed manageable (I was young). I bought makeup and had the salesperson teach me how to apply it (foundation, mascara, eyeliner and lipstick). As for my weight, I had no idea how to diet. The idea of dieting had never entered my consciousness. I did what seemed logical. I ate half of what I usually ate and I quickly lost thirty pounds. One day, I walked into the psych unit and another counselor said, “Wow, Dierdra, you’re a mere shadow of your old self.”

From that point on, Morty took me to all my firsts–first ballet, first play, first musical, and first plane ride. The first play/musical he took me to was Golden Boy with Sammy Davis, Jr. I was thrilled. I had never been to a live show before and I thought Sammy Davis was the greatest entertainer who ever lived. He could sing, dance, act, play several instruments, and impersonate other famous people. He was also black and I’d never seen a black entertainer up close. I was in minority heaven. Morty also took me to see Hair at the Public Theatre off-Broadway, the Royal Ballet and the Bolshoi Ballet at the New York State Theatre at Lincoln Center, and the operas, Tosca, Don Giovanni, Madama Butterfly, and Antony and Cleopatra at the Met. Each time we went somewhere, he asked me, with great anticipation, what I thought of the performance and the theatre where it was held. It was as if he chose the particular show in anticipation of my response, which was always positive if not overly exuberant. “I love it (referring to the performance). It’s all right (referring to the theatre).”

One time we went to see the Whirling Dervishes at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. For those unfamiliar with the Dervishes, a dervish is a mystical dancer who stands between the material and cosmic worlds. His dance is part of a sacred ceremony in remembrance of God. The dervish rotates in a precise rhythm, representing the Earth revolving on its axis while orbiting the sun. The purpose of the ritual whirling is for the dervish to empty himself of all distracting thoughts, placing him in trance; released from his body, he conquers dizziness. (www.gregangelo.com). I knew nothing about the Dervishes then, and Morty had not educated me. Had I known that the whirling was a sacred dance in remembrance of God, I might have tried harder to control what happened as the Dervishes started to Whirl. Their skirts slowly lifted, fanning out like a dish spinning on a pole. A profound silence fell over the theatre, when I suddenly heard my watch ticking. “TICK, TICK, TICK, TICK, TICK, TICK.” It was the loudest sound I ever heard. Even Morty heard it. I suddenly felt this wellspring of emotion rising in my body. I couldn’t keep it down. It bubbled out of me and suddenly I was laughing hysterically, tears streaming down my face, and I couldn’t stop. I looked over at Morty. His shoulders were rising and falling and his face was red. Suddenly this awful high-pitched sound shot out of him. He too was laughing hysterically. I put my hand over my watch, but I could still hear it ticking. To top it off, it was a Mickey Mouse watch, which made it even funnier. In a flash, a bright light was shining in our faces and an usher was asking us to leave the theatre, which, of course, we did. We ran up the aisle unable to control ourselves, heads turning to watch us as we left. I could barely walk because I was wetting my pants from laughing so much. I had to find a bathroom in a hurry. That was a memorable evening. One of the things I enjoyed about Morty was his sense of humor. It was like mine. He had an appreciation for the ridiculous. We spent many an evening laughing hysterically over silliness.

Morty had peculiar eating habits. Whenever he ate ice cream, he dumped a mountain of sugar on top of it. He added sugar to most of his desserts. He found out many years later that he was diabetic. Whenever we ate out, he left the table littered with food. He ate quickly and food flew out of his mouth as he was talking or chewing. It was like a food war zone. I found myself bobbing and weaving to avoid morsels of food. By the time he finished eating, our table looked as if we’d had a food fight. In the beginning, I used to try to clean up the table before the waiter came with the check. After a while, I got used to having food all over the table, the floor, and occasionally the wall, so I left the cleanup to the busboy.

For the most part, when we went about town, people didn’t notice us. However, one time, in Greenwich Village of all places, a deranged black man approached Morty, throwing punches and repeatedly screaming, “You stealing black women, you son of a bitch!” Morty was the nervous type and didn’t respond well to any sort of confrontation. He fumbled and stuttered and tripped. I suggested that we run in the opposite direction, which we did. We never talked about what happened that evening and it never happened again.

In the summer, I spent my weekends with Morty on Fire Island in the Pines. The first summer he rented a house. Every subsequent summer, he rented a condo. We traveled to Fire Island by train and ferry. The Pines is an upscale, essentially gay community, with beautiful homes and condos along the boardwalk and on the beach. Morty seemed asexual to me. I think he chose the Pines because it was less hectic than the other Fire Island communities and he liked to be part of the upscale scene, even if only temporarily. He liked interesting people, places and events, and was willing to spend money on all of them. (Yet, he was frugal, and lived in a small Brooklyn Heights apartment, where he cared for both his invalid parents until their deaths). He was curious about everything and loved to be surrounded by beautiful people. When we first went to the Pines together, people thought we were a couple, albeit an odd one.

The first house Morty rented was a big red structure that looked like a barn. It was on the bay side of the island. The interior was dark and musty and a swing hung from the ceiling in the living room. The back walls of the living room opened up so that you could swing out over the bay. That swing was the best thing about that house. We never ate there. It was too creepy and at night it was spooky. After that first season, Morty rented a condo on the ocean side. It was a bright and sunny studio apartment and we each slept on a separate couch-bed. I cooked our meals in that apartment and cleaned the place spotless before we left each weekend. I did such a thorough job of cleaning at the end of the summer that the people who owned the condo held it for us each season. Cooking and cleaning seemed a small price to pay for weekends outside the hustle, bustle, and humidity of the city. I loved those summers. Morty liked people, and in spite of his stuttering, he did not hesitate to introduce himself and me to anyone who struck his fancy. I learned to open up to people during those summers.

Morty also introduced me to a world of words and entertainment that had alluded me prior to that time—the works of Norman Mailer, Truman Capote, and other great authors. He and I watched David Susskind, William F. Buckley (both of whom I thought were snobs) and other conservative and not so conservative pundits, entranced by their intellect, but not their politics, which were diametrically opposed to ours. I had a natural gift for words, but, thanks to Morty, my capacity for self-expression and vocabulary grew. On the other hand, Morty had a bad habit of making me feel as if he always expected less of me by acting surprised when I performed better than he expected. For example, while at the performance of Hair, another patron, who was a friend of Morty’s, said, “Are you Dierdra?” I answered, “Yes, I’m she.” Morty loudly complimented me on my grammatical savvy. It was not unusual for him to register surprise whenever I said something grammatically sophisticated. I wasn’t ungrammatical generally. I had a natural gift for grammar, so his surprise suggested snobbishness on his part and I grew to resent it.

As the years passed, Morty and I took trips together, which he always paid for. One time, we went to Puerto Rico, where he stayed at one hotel and I stayed at another. I have no idea why we stayed at separate hotels, but we did. We’d meet in the mornings, have breakfast together and then spend the rest of the day either roaming around the island or sunbathing. Our relationship was strictly platonic. To Morty, I was a work in progress. However, one time as we were parting ways on the subway after an evening out, he said, “I’m going on vacation for two weeks. Aren’t you going to kiss me goodbye?” I was taken aback and then kissed him on the cheek. He seemed satisfied and never asked me to do that again.

Working at the Professional Placement Center was a gift. As a rule, the professional staff did not fraternize with the support staff. However, where I was concerned, fraternization was the rule. In those days, I had a quality that I was unaware of. It drew the professional staff to me. I surmise that they saw my potential. They were invested in my growth. A couple of the professional women taught me how to coordinate my clothing and my accessories. Another became a good friend and invited me to dinner with her and her husband at their apartment. I stopped accepting those invitations when her husband made a pass at me.

When I reported for work on my 21st birthday, my desk was filled with miniature stuffed animals. I used to collect them and each counselor bought me one for my birthday, something one of the other clerical staff told me had never happened to any support staff member before. The next year no one remembered that I had already had my 21st birthday, so I claimed to be twenty-one again. I didn’t want to grow up. I was enjoying being taken care of.

Eventually, my boss, Mr. “B,” convinced me to go back to school. He felt I was wasted doing clerical work. “Dierdra, you should be doing more than greeting people at the front desk and filing application forms. You make filing mistakes because you’re bored. Go back to school. You’re too smart for this job.” After six years of telling me the same thing, I took his advice to heart and applied to college through an anti-poverty program. I scored high on aptitude tests and was immediately accepted into the regular college program, meaning I needed no remediation or special help. I received a stipend and free tuition, books and supplies.

I left the Professional Placement Center when I entered college, and over time, my friendships faded. I got busy with my studies, moved out of my mom’s place, took jobs cleaning apartments, and had little time to socialize or keep in touch. I eventually lost all contact with my friends at the Professional Placement Center, including Morty. I graduated from college summa cum laude and applied to law school, not because I wanted to be a lawyer, but because I did not know what else to do to make money. My goal was never to have to live in the projects, which is where I grew up. I was a lawyer the next time I ran into Morty. He was working as a hospital administrator, and, as was his practice, had formed friendships with the black support staff there. Much of our conversation was about the support staff—who they were, what they were like, etc. I think anyone who was not like Morty fascinated him. I wondered whether he had changed in any respect. He seemed stuck in time. We went out to dinner on a subsequent night and on the way to our table, I saw someone who had been hired by my boss to restructure the law office at the Board of Education, making office assignments that were more efficient and collegial. I went over to the table to hug and speak to the person, and then I introduced Morty to him. When we finally went to our table, Morty said, “I can’t get over how sophisticated you are. You’re so glib and articulate.” Nothing had changed. We eventually drifted apart for good.

It is said that people come into your life for a reason, a season, or a lifetime. When you figure out which it is, you know exactly what to do. I believe Morty entered my life for a reason and a season. When I met Morty, I was shy and had never been anywhere. He helped fulfill my unexpressed desire to be worldly, to see things I thought I’d never see, and to show me that I was smarter than I believed. As I evolved, our season together slowly came to an end. In some sense, he is with me for a lifetime too, because the things he brought into my life shaped me and will never leave me. I love him, but I never told him so. I wish I had.

Daddy Ken

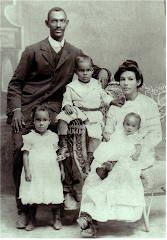

In the late 1940’s, mom had been divorced from my

father for at least four years. Their marriage was born out of necessity, not

love, and it was doomed from the beginning. So, she was raising five children

on her own without assistance from my father, who never sent her the

court-ordered child support. Mom had neither the desire nor the resources to

seek enforcement of the support. She was just glad to have my father out of her

life. We lived in the projects in Long Island City and were on the dole for a

few years after the divorce. Mom eventually found work in a factory.

On a bright sunny day in June 1949, mom was on the

subway, returning home from work when she met someone who would change her life.

She was 37 years old and looked 25, vibrant and petite. She had mocha colored

skin, dark curly hair, and a face punctuated by high cheekbones and

arched eyebrows. In other words, she was eye candy. Mom was preoccupied

with what she would make for dinner that evening and thought she had missed her

stop. She craned her neck to see exactly how far along in her trip she was,

when her eyes met a young man’s. He was holding a cake box and leaning against

the subway car door. He smiled and mom immediately lowered her head, a slight

smile on her face. The young man, who was tall, lean and handsome, with dark

wavy hair, sharp features, piercing dark eyes, and a crooked smile, was twelve

years mom’s junior and was either Italian or Spanish. He slowly moved toward mom,

grabbing the strap hanger just above her head. He was about to speak when the

train pulled into the station and stopped with a lurch, sending the cake box

flying.

The box opened and the cake spilled out onto mom’s

dress. She jumped up, catching the cake, which broke into two pieces. The young

man apologized profusely, gathering up what he could of the cake and putting it back in the

box. Mom brushed off her dress and said it was okay. The train pulled into her

stop and she rose to exit the car, with the young man in pursuit. As she headed

for the stairs, the young man ran behind her, asking her if she would let him

pay to dry clean her dress. Mom smiled again and said it was all right, that

he didn’t have to bother. The young man persisted and followed her down the

stairs, introducing himself: “My name is Kenneth Pietra.” It was a long walk

from the subway to the projects. Mom and the young man walked from Queensboro

Plaza to 21st Street, and all the way through the projects to Vernon Blvd. All the

time, the young man pleaded his case to pay for the cleaning of the dress,

while asking mom what her name was. Mom said, “Linnette,” her heart beating

rapidly. He touched her arm and said, “May I see you again or at least call

you?” Mom’s body reacted to his touch and she hoped that it didn’t show. By the

time they reached our apartment building mom relented and gave the young man

her phone number, but refused money to dry clean her dress. She knew from the

moment she set eyes on him that she loved him and she knew that he loved her.

This young man, Ken, called the next day and

appeared at our door the following weekend. Mom was excited and nervous about

her first date with Ken. When he arrived at the apartment, he had a bouquet of

flowers and mom invited him in. She introduced him to us kids and we all ate

dinner together. After we went to bed, mom and Ken sat in the living room and

talked for hours. He kissed her passionately good night at the end of the

evening. He returned almost every weekend and sometimes during the week. We

were always thrilled to see him. Mom was a changed woman. Suddenly, life was

full in a way it had not been up until that point. She had found someone who

loved her as a woman. She was feeling mature love for the first time in her

life. She and Ken had a tender yet passionate relationship. It was a love

affair that would fill mom like nothing had before. It would also bring a new

life into the world along with tremendous heartache.

We kids called him “Daddy Ken.” We loved him. He

was kind, generous and loving. My sister thought he would have made a wonderful

father for us. He paid attention to mom and gave us kids just as much

attention. He was fun to be around and seemed to genuinely love us. Mom smiled

a lot in that relationship. She walked differently, with a skip in her step. I

saw utter joy in her expression and I loved it. I loved Ken for putting that

expression there. Ken often helped mom cook and introduced her to Italian

cooking. He played games with us, took us to the park, ate mom’s cooking, and

brought us kids toys and other gifts. He read us stories and treated us as if

we were his own. “Daddy Ken” was an appropriate title for him. Ken knew mom was

having a hard time making ends meet, so he always gave her money instead of

gifts. Mom was mortified that he would give her money. I think it made her feel

less than, even though that was not Ken’s intention. My sister and I had never

seen mom as happy as she was then. It was the best time of our lives.

Mom and Ken had been dating for about a year, when,

one night, in a moment of passion, mom did not use her diaphragm. She told me

that it was the only time she ever had sex with Ken in our apartment. That

night would result in the longest lasting memory of Ken mom would ever have.

In the meantime, things were in turmoil in Ken’s

life. His mother was lobbying against the relationship, not because mom was

black, nor because of her age, but because she already had five kids. Ken

wanted to marry mom, but his mother was against it. She sabotaged the relationship. Under tremendous

pressure from his mother, who feigned illness and threatened to kill herself if

he didn’t stop seeing mom, Ken reluctantly broke off the relationship, not

realizing that mom was pregnant. Mom was stunned and confused. I could hear her

sobbing in her bedroom at night. I felt lost. I missed Ken and I longed for my

mother to feel better. I was convinced that I had done something to drive Ken

away. After all, my father abandoned the family too, leaving my mother

destitute with five mouths to feed. Now it was happening again. I bore that

burden all of my childhood, and, to make up for mom’s loss, I became my

brother, Michael’s, caretaker, so much so that mom used to say that I raised

him.

Michael was born on October 9, 1951. Mom had him at

a time when having a baby out of wedlock was still taboo. Nevertheless, she

doted on Michael, who was the spitting image of his father. She dressed him in

the best clothes and kept his shoes polished. Mom went back to work when

Michael was about three years old; so he attended the nursery school in the

projects. I was a latchkey kid and used to pick him up after school and bring

him home. My mother never stopped loving Ken and sent him letters, along with

Michael’s baby pictures, his first pair of shoes, a lock of his hair, and all

of his school pictures, but Ken never responded. Mom’s heart was irreparably

broken, but the flame still burned. Michael was a constant reminder of that

lost love, and mom’s love for him, like that for his father, was undying.

Ken found out that mom had a baby about three or

four years after Michael was born. By then, mom was in another marriage. She

had married my stepfather on the rebound and paid a heavy price, but that’s

another story. One day, Ken showed up at the apartment, looking for my mother

and his son. My sister, who was 12 1/2 years old at the time, answered the

door, but wouldn’t tell him where my mother worked, and informed him that mom

was married. My sister was afraid that Ken would take my brother with him, so

she would not say where Michael was. She stressed that he was not in the

project nursery school either. That was enough to convince Ken that that was

precisely where he was. So, on his way out of the projects, Ken stopped off at

the nursery school and asked to see Michael, explaining that he was Michael’s

father. The director of the nursery school, who was an old friend of my

mother’s, denied his request. Ken left a broken man, never to return. Mom found

out about the visit, but thought better of trying to contact him. After all,

she was married and was trying to make that work.

Mom had given Michael my father’s last name, even

though she and my father had divorced almost five years earlier. Michael had no

relationship with my father. On the rare occasion that my father did show up,

he completely ignored Michael. The man my mother married after Ken left was a

drunk and a brute, who showed no affection toward any of us, including my

mother. Michael still carries the scars from not knowing his father. He was a

lost child in many ways, acutely aware that his “real” father was missing from

his life without explanation and that he was unloved by the man whose name he

carried and the man who was supposed to be his stepfather. Thirty years after

Ken left, mom received a call from a woman who said she was Ken’s sister. His

family was looking for him and thought he had been with my mom all those years.

They wanted to let him know that his mother had died. Apparently, Ken found out what his mother had done (hiding all the letters and other mementos mom sent him), had a

falling out with his mother over the fact that she had interfered in his

relationship with mom, and caused him to lose the love of his life and his

child, so he cut off all ties with her and the rest of his family. He had been

estranged from them all those years.

Ken’s sister told my mother that their mother

had not destroyed mom’s letters, but had hidden them from Ken. They found mom’s

phone number, which hadn’t changed in thirty years, in one of the letters. Mom

informed them that she hadn’t seen Ken in thirty years. That was the last

contact she had with any of his family. A few months before mom died, she said

that she knew that she’d see Ken “on the other side.” She reflected on her life

and said that she “had a pretty good life.” I was floored by that comment,

because I knew that heartache was a theme that ran through her life. She simply

didn’t see it that way. She saw each painful event as an opportunity to evolve

and she did evolve. She died a loving, joyful and much loved woman.

.jpg)